Cyber Threat Intelligence Specific Sources

In this post, we’ll look into the sources, agencies, and tools commonly used in the cyber threat intelligence (CTI) life cycle and discuss the criteria the analyst can follow to select them.

Sources are the defined methods through which data is collected. Agencies are organizations that provide intelligence and leverage sources. Both vary in terms of scope, cost, credibility, and accuracy. Regardless, it’s common practice for agencies to share intelligence on the web freely. Examples of such agencies include CrowdStrike, Mandiant, ThreatMiner, and Recorded Future.

Three primary CTI sources are domain information (WHOIS), passive DNS, and malware databases. Each of these has specificities that are worth highlighting separately.

- WHOIS performs domain lookups, returning IP addresses, identification, and contact information of registrars and registrants (e.g., e-mail, phone number, and mailing address). This source can be considered a doorway into the threat actor infrastructure, possibly exposing essential elements such as staging and C2 servers. Since the domain owner provides its data, adversaries can decide not to include any compromising information or even opt for deception, publishing bogus data. This is possible because registrars don’t check the validity of the data. However, it’s worth noting that threat actors may repeatedly use the same false information on multiple domains (especially if there are many), producing a behavioral pattern helpful for attribution.

- Domain names and IP address associations often change, and techniques such as fast flux DNS (a specific domain cycles through various IP addresses) are used by threat actors to evade detection, outdating DNS lookup results as quickly as possible. Passive DNS, a record that DNS servers hold, is advantageous since it provides the CTI team with the history of associations between domains’ names and IP addresses, circumventing such quick changes.

- Malware data is often obtained in databases that aggregate information from reverse engineering (e.g., compilation date, type of programming language, file name, and hashes). VirusTotal, Hybrid Analysis, and Malware Bazaar are three of the most well-known malware database examples.

Additional sources include sites that indicate possible data compromise, like “Have I Been Pwned?” and ports that may be open to the Internet. Shodan is the leading example of this last category.

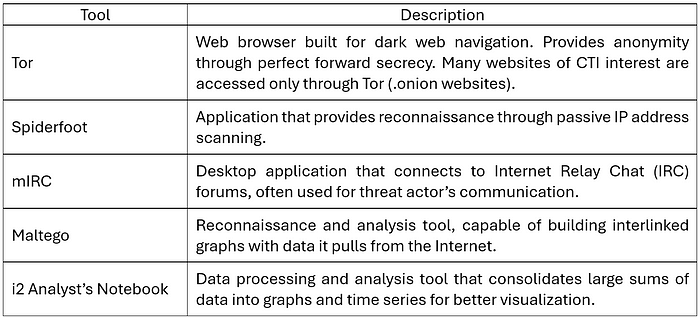

Aside from sources and agencies, the CTI analyst uses tools that optimize data collection and processing into information. Such tools range from specialized web browsers to social network analysis, as illustrated in the table below:

The CTI team must use specific techniques to extract the most from the available sources and tools. These include implementing specific search mechanisms (e.g., Google Dorks), regular expressions (regex), and YARA rules. A central approach is pivoting (discussed in-depth in a previous post on the Diamond Model), which consists of moving from one source or agency to another following the logical links between the collected data and informational gaps. Pivoting provides greater insight that wouldn’t be possible from a single SANDA.

After operationalizing Intelligence Requirements (IRs/PIRs) into Requests for Information (RFIs), it’s fundamental to use the correct criteria for choosing the appropriate SANDA and tools. One such methodology (discussed in a previous post) was to map SANDAs to specific threat actors’ objectives, capabilities, and infrastructure. So, for example, since hacktivists are pretty active on platforms such as X and specific blogs, social media aggregators are an excellent SANDA option. At the same time, passive DNS and WHOIS are a good fit for APTs and cybercriminals. But there are other criteria which can be an alternative or used in combination with other selection references:

- Associate SANDAs with distinct Cyber Kill Chain stages and the Diamond Model’s features and meta-features. Tools such as Maltego and Spiderfoot can model the Reconnaissance stage. Malware-centric sources like VirusTotal help gather data to describe the Weaponization, Delivery, and Exploitation stages. Agencies reports give insights into threat actors’ posture before and after the attack, including their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), the infrastructure at their disposal, and the objectives they wish to accomplish. The Diamond Model pivoting approaches further refine collection efforts.

- Budget and scope constraints may limit the availability of SANDA/tools to the CTI team. For example, agencies often prefer particular threat actors, and not every OSINT source or tool is free of charge (e.g., Maltego’s paid option).

The challenge here is to minimize intelligence gaps by establishing SANDA/tool redundancy as much as possible while avoiding data excess, which can hamper analysis. In that sense, the CTI team may have secondary/minor SANDA/tools in case of access failure to primary/main ones. If the team doesn’t have direct access to a specific source (e.g., because of budget), it may access an agency’s free intelligence report that leverages this source.